I have always delighted in learning about the lives of others, and have tried to incorporate as many memoirs into my reading as is possible. I enjoy reading about individuals, particularly women, whose lives are very different to my own, and always find this a highly enriching experience. With this in mind, I have gathered together five wonderful memoirs of women which I have read of late, and which I would highly recommend. There are illness narratives, translated books, works set during wartime, and quiet meditations in the list, and I dearly hope that you find something new to pick up.

1. The Bright Hour: A Memoir of Living and Dying by Nina Riggs *****

1. The Bright Hour: A Memoir of Living and Dying by Nina Riggs *****

‘An exquisite memoir about how to live–and love–every day with “death in the room,” from poet Nina Riggs, mother of two young sons and the direct descendant of Ralph Waldo Emerson, in the tradition of When Breath Becomes Air. Nina Riggs was just thirty-seven years old when initially diagnosed with breast cancer–one small spot. Within a year, the mother of two sons, ages seven and nine, and married sixteen years to her best friend, received the devastating news that her cancer was terminal. How does one live each day, “unattached to outcome”? How does one approach the moments, big and small, with both love and honesty? Exploring motherhood, marriage, friendship, and memory, even as she wrestles with the legacy of her great-great-great grandfather, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nina Riggs’s breathtaking memoir continues the urgent conversation that Paul Kalanithi began in his gorgeous When Breath Becomes Air. She asks, what makes a meaningful life when one has limited time? Brilliantly written, disarmingly funny, and deeply moving, The Bright Hour is about how to love all the days, even the bad ones, and it’s about the way literature, especially Emerson, and Nina’s other muse, Montaigne, can be a balm and a form of prayer. It’s a book about looking death squarely in the face and saying “this is what will be.” Especially poignant in these uncertain times, The Bright Hour urges us to live well and not lose sight of what makes us human: love, art, music, words.‘

2. When a Toy Dog Became a Wolf and the Moon Broke Curfew by Hendrika de Vries  ****

****

‘Born in the Netherlands at a time when girls are to be housewives and mothers and nothing else, Hendrika de Vries is a “daddy’s girl” until her father is deported from Nazi-occupied Amsterdam to a POW camp in Germany and her mother joins the Resistance. In the aftermath of her father’s departure, Hendrika watches as freedoms formerly taken for granted are eroded with escalating brutality by men with swastika armbands who aim to exterminate those they deem “inferior” and those who do not obey. As time goes on, Hendrika absorbs her mother’s strength and faith, and learns about moral choice and forced silence. She sees her hidden Jewish “stepsister” betrayed, and her mother interrogated at gunpoint. She and her mother suffer near starvation, and they narrowly escape death on the day of liberation. But they survive it all—and through these harrowing experiences, Hendrika discovers the woman she wants to become.‘

3. The Book Collectors: A Band of Syrian Rebels and the Stories That Carried Them Through a War by Delphine Minoui ****

3. The Book Collectors: A Band of Syrian Rebels and the Stories That Carried Them Through a War by Delphine Minoui ****

‘Award-winning journalist Delphine Minoui recounts the true story of a band of young rebels in a besieged Syrian town, who find hope and connection making an underground library from the rubble of war. Day in, day out, bombs fall on Daraya, a town outside Damascus, the very spot where the Syrian Civil War began. In the midst of chaos and bloodshed, a group searching for survivors stumbles on a cache of books. They collect the books, then look for more. In a week they have six thousand volumes. In a month, fifteen thousand. A sanctuary is born: a library where the people of Daraya can explore beyond the blockade. Long a site of peaceful resistance to the Assad regimes, Daraya was under siege for four years. No one entered or left, and international aid was blocked. In 2015, French-Iranian journalist Delphine Minoui saw a post on Facebook about this secret library and tracked down one of its founders, twenty-three-year-old Ahmad, an aspiring photojournalist himself. Over WhatsApp and Facebook, Minoui learned about the young men who gathered in the library, exchanged ideas, learned English, and imagined how to shape the future, even as bombs fell above. They devoured a marvelous range of books–from American self-help like The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People to international bestsellers like The Alchemist, from Arabic poetry by Mahmoud Darwish to Shakespearean plays to stories of war in other times and places, such as the siege of Sarajevo. They also shared photos and stories of their lives before and during the war, planned how to build a democracy, and began to sustain a community in shell-shocked soil. As these everyday heroes struggle to hold their ground, they become as much an inspiration as the books they read. And in the course of telling their stories, Delphine Minoui makes this far-off, complicated war immediate. In the vein of classic tales of the triumph of the human spirit–like All the Beautiful Forevers, A Long Way Gone, and Reading Lolita in Tehran—The Book Collectors will inspire readers and encourage them to imagine the wider world.‘

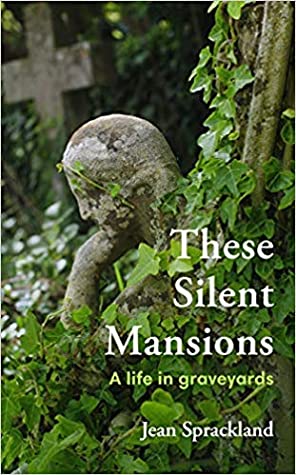

4. These Silent Mansions: A Life in Graveyards by Jean Sprackland ****

‘Graveyards are oases: places of escape, of peace and reflection. Each is a garden or nature reserve, but also a site of commemoration, where the past is close enough to touch: a liminal place, at the border of the living world. Jean Sprackland’s prize-winning book, Strands, brought to life the histories of objects found on a beach. These Silent Mansions is also an uncovering of individual stories: vivid, touching and intimately told. Sprackland travels back through her own life, revisiting graveyards in the ordinary towns and cities she has called home, seeking out others who lived, died and are remembered or forgotten there. With her poet’s eye, she makes chance discoveries among the stones and inscriptions: a notorious smuggler tucked up in a sleepy churchyard; ancient coins unearthed on a secret burial ground; a slow-worm basking in the sun. These Silent Mansions is an elegant, exhilarating meditation on the relationship between the living and the dead, the nature of time and loss, and how – in this restless, accelerated world – we can connect the here with the elsewhere, the present with the past.‘

5. Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul by Taran N. Khan ****

5. Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul by Taran N. Khan ****

‘For most Indians, Kabul is a city that is near, yet far-familiar, yet unknown. When Taran N. Khan arrived in Kabul in the spring of 2006, five years after the overthrow of the Taliban regime, she was earnestly cautioned never to walk. Her instincts compelled her to do the opposite: to take that precarious first step and enter the life of the city with the unique, tactile intimacy that comes from being a walker. She didn’t stop until 2013, when she returned to India. In Shadow City, Taran N. Khan paints a lyrical, personal, and meditative portrait of a city we know primarily in terms of conflict and peace. As a Muslim woman raised in a small town in India, Taran discovered that she had access to parts of Kabul uncharted by travellers before her. The result reads like an elegiac prose map of the city, rich with surprises-from the glitter of wedding halls that shine like a bizarre version of Las Vegas; to the mental health hospital where women are abandoned and isolated but exist in a rare space of freedom and solitude; to the bookseller behind The Bookseller of Kabul, who sued Åsne Seierstad for her portrayal of him and then published the rebuttal which he displays proudly in his shop window.‘

1. The Bright Hour: A Memoir of Living and Dying by Nina Riggs *****

1. The Bright Hour: A Memoir of Living and Dying by Nina Riggs ***** ****

**** 3. The Book Collectors: A Band of Syrian Rebels and the Stories That Carried Them Through a War by Delphine Minoui ****

3. The Book Collectors: A Band of Syrian Rebels and the Stories That Carried Them Through a War by Delphine Minoui ****

5. Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul by Taran N. Khan ****

5. Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul by Taran N. Khan **** ‘Healing’. She gives her account chronologically, and makes clear in her introduction that she only began to write her memoir in 1980, whilst working as a psychologist. Of her troubled patient Jason, whom she also introduces here, she finds so much wholly applicable to her own past: ‘… despite our obvious differences, there was much we shared. We both knew violence. And we both knew what it was like to become frozen. I also carried a wound within me, a sorrow so deep that for many years I hadn’t been able to speak of it at all, to anyone.’

‘Healing’. She gives her account chronologically, and makes clear in her introduction that she only began to write her memoir in 1980, whilst working as a psychologist. Of her troubled patient Jason, whom she also introduces here, she finds so much wholly applicable to her own past: ‘… despite our obvious differences, there was much we shared. We both knew violence. And we both knew what it was like to become frozen. I also carried a wound within me, a sorrow so deep that for many years I hadn’t been able to speak of it at all, to anyone.’ The heroine of the piece, Juliet Armstrong, is ‘reluctantly recruited into the world of espionage’ during the Second World War. ‘Sent to an obscure department of MI5 tasked with monitoring the comings and goings of British Fascist sympathizers, she discovers the work to be by turns both tedious and terrifying.’ Once the war finishes and Juliet’s contract is terminated, she tries to put the experience firmly behind her.

The heroine of the piece, Juliet Armstrong, is ‘reluctantly recruited into the world of espionage’ during the Second World War. ‘Sent to an obscure department of MI5 tasked with monitoring the comings and goings of British Fascist sympathizers, she discovers the work to be by turns both tedious and terrifying.’ Once the war finishes and Juliet’s contract is terminated, she tries to put the experience firmly behind her. The protagonists of the piece are two women, Rene Hargreaves and Elsie Boston. Rene is billeted to the rural Starlight Farm in Berkshire, far from her home in Manchester, in the summer of 1940. At first, she finds Elsie ‘and her country ways’ decidedly odd. However, once the women come to know one another, a mutual understanding and dependence is formed. Their life with one another is quiet, almost idyllic, until the peace is shattered by the arrival on Starlight Farm of someone from Rene’s past. At this point, they face trials which endanger everything which they have built, ‘a life that has always kept others at a careful distance.’

The protagonists of the piece are two women, Rene Hargreaves and Elsie Boston. Rene is billeted to the rural Starlight Farm in Berkshire, far from her home in Manchester, in the summer of 1940. At first, she finds Elsie ‘and her country ways’ decidedly odd. However, once the women come to know one another, a mutual understanding and dependence is formed. Their life with one another is quiet, almost idyllic, until the peace is shattered by the arrival on Starlight Farm of someone from Rene’s past. At this point, they face trials which endanger everything which they have built, ‘a life that has always kept others at a careful distance.’