I purchased The Name of the Rose, my first taste of Umberto Eco’s work, quite some time before I read it. Whilst the plot appealed to me, and I had heard nothing but good things about the novel, I kept putting it off in favour of shorter books which would be easier to finish. However, I picked it up over a relatively free weekend, where I was able to dedicate some time to it.

First published in Italian in 1980, The Name of the Rose is set in the Middle Ages – in 1327, to be precise. The Vintage edition which I read was translated by William Weaver. Of the novel, the Financial Times comments: ‘The late medieval world, teetering on the edge of discoveries and ideas that will hurl it into one more recognisably like ours… evoked with a force and wit that are breathtaking.’

At the beginning of the novel, Franciscan monk Brother William of Baskerville ‘arrives at a wealthy Italian abbey on theological business.’ His ‘delicate mission’, which we are not at first party to, becomes ‘overshadowed by seven bizarre deaths’. Brother William chooses to turn detective, exploring the ‘eerie labyrinth of the abbey, where extraordinary things are happening under the cover of the night.’ Lucky for Brother William, he has Sherlockian powers of deduction, and is able to make sense of the most obscure occurrences. The whole is narrated by his scribe and ‘disciple’, Adso of Melk. The novel, says its blurb, is ‘not only a narrative of a murder investigation but an astonishing chronicle of the Middle Ages.’

The novel is introduced by an omniscient narrator in 1968. They have just been handed a book which claims to reproduce a fourteenth-century manuscript in its entirety. This narrator goes on to say: ‘In a state of intellectual excitement, I read with fascination the terrible story of Adso of Melk, and I allowed myself to be so absorbed by it that, almost in a single burst of energy, I completed a translation, using some of those large notebooks from the Papeterie Joseph Gilbert in which it is so pleasant to write if you use a felt-tip pen.’

Even Adso is not told of Brother William’s mission: ‘… [It] remained unknown to me while we were on our journey, or, rather, he never spoke to me about it. It was only by overhearing bits of his conversations with the abbots of the monasteries where we stopped along the way that I formed some idea of the nature of this assignment. But I did not understand it fully until we reached our destination.’ He finds Brother William rather an imposing figure: ‘… [He] was larger in stature than a normal man and so thin that he seemed still taller. His eyes were sharp and penetrating; his thin and slightly beaky nose gave his countenance the expression of a man on the lookout…’.

The context and social conditions in The Name of the Rose are rich and wonderfully executed. I found the novel transporting from its beginning. Eco has included much about libraries, scribes, and manuscripts, elements of the Middle Ages which fascinate me. Several reviews which I have seen have commented upon the complicated language and long, meandering sentences used by the author. I personally did not find this a problem, and got into the style very quickly; I felt as though it added another layer of texture to the novel, making it feel more old-fashioned, and therefore perhaps more authentic. Eco’s prose, and the way it has been rendered in this translation, is engaging.

Eco’s descriptions, of which there are many, also capture a lot: ‘It was noon and the light came in bursts through the choir windows, and even more through those of the façade, creating white cascades that, like mystic streams of divine substance, intersected at various points of the church, engulfing the altar itself.’ The use of colour and touch woven throughout help to build a believable, and atmospheric, sense of place. Eco’s dialogue also has such strength to it, and never did it feel predictable. I particularly liked the way in which William spoke. He tells Adso, for instance: ‘The story is becoming more complicated, dear Adso… We pursue a manuscript, we become interested in the diatribes of some overcurious monks and in the actions of other, over-lustful ones, and now, more and more insistently, an entirely different trail emerges.’

The Name of the Rose definitely feels like a good, and popular, choice to begin with with regard to Eco’s works. I really enjoyed the structure of the novel; it is told over the course of seven days. So many layers have been built on top of one another; its foundations are strong, and the separate strands of plot all interesting in their own way. The novel takes many twists and turns, and is such a compelling read. Eco takes one down so many avenues of intrigue, meeting strange and complex characters along the way. My only criticism of the novel is that some of the chapters, particularly toward the middle of the novel, felt superfluous, and added very little to the story aside from religious context. Some events are a little dramatic in places, but it was all drawn together well, and on the whole, I really enjoyed it.

I have read comparatively little set during the Middle Ages, despite the fact that the period fascinates me. Reading The Name of the Rose has certainly made me want to seek out more novels set between the fifth and fifteenth centuries, and to try another of Eco’s books too.

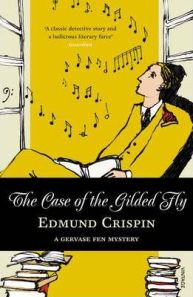

The Guardian praise Edmund Crispin’s series of crime novels as ‘a ludicrous literary farce’, and The Times call the author ‘one of the last exponents of the classical English detective story… elegant, literate, and funny.’ In this, the first novel in the series, a ‘pretty but spiteful young actress’ named Yseut Haskell, who has a ‘talent for destroying men’s lives’, is discovered dead in a University room ‘just metres from unconventional Oxford don Gervase Fen’s office.’ In rather an amusing aside, the blurb says: ‘Anyone who knew her would have shot her, but can Fen discover who could have shot her?’

The Guardian praise Edmund Crispin’s series of crime novels as ‘a ludicrous literary farce’, and The Times call the author ‘one of the last exponents of the classical English detective story… elegant, literate, and funny.’ In this, the first novel in the series, a ‘pretty but spiteful young actress’ named Yseut Haskell, who has a ‘talent for destroying men’s lives’, is discovered dead in a University room ‘just metres from unconventional Oxford don Gervase Fen’s office.’ In rather an amusing aside, the blurb says: ‘Anyone who knew her would have shot her, but can Fen discover who could have shot her?’ that Resorting to Murder ‘shows the enjoyable and unexpected ways in which crime writers have used summer holidays as a theme’. The tales have a wide range across the Golden Age of British crime fiction, encompassing both ‘stellar names from the past’ and uncovering ‘hidden gems’. Edwards believes that some of the stories which he has selected for publication within the volume are ‘obscure’ and ‘rare’, and have ‘seldom been reprinted’. Well-known authors such as Arthur Conan Doyle, Arnold Bennett and G.K. Chesterton thus sit alongside the lesser-known likes of Basil Thomson, Leo Bruce and Gerald Findler.

that Resorting to Murder ‘shows the enjoyable and unexpected ways in which crime writers have used summer holidays as a theme’. The tales have a wide range across the Golden Age of British crime fiction, encompassing both ‘stellar names from the past’ and uncovering ‘hidden gems’. Edwards believes that some of the stories which he has selected for publication within the volume are ‘obscure’ and ‘rare’, and have ‘seldom been reprinted’. Well-known authors such as Arthur Conan Doyle, Arnold Bennett and G.K. Chesterton thus sit alongside the lesser-known likes of Basil Thomson, Leo Bruce and Gerald Findler.

The Mind’s Eye is the first Inspector van Veeteren mystery, in which a history and philosophy teacher named Janek Mitter awakes to find that he cannot remember who he is. He then discovers the body of his beautiful young wife, Eva, floating in the bath after an attack. Even during the trial which follows, he has no memory of attacking his wife, or any idea as to how he could have killed her; indeed, ‘Only when he is sentenced and locked up in an asylum for the criminally insane does he have a snatch of insight. He scribbles something in his Bible, but is murdered before the clue can be uncovered’.

The Mind’s Eye is the first Inspector van Veeteren mystery, in which a history and philosophy teacher named Janek Mitter awakes to find that he cannot remember who he is. He then discovers the body of his beautiful young wife, Eva, floating in the bath after an attack. Even during the trial which follows, he has no memory of attacking his wife, or any idea as to how he could have killed her; indeed, ‘Only when he is sentenced and locked up in an asylum for the criminally insane does he have a snatch of insight. He scribbles something in his Bible, but is murdered before the clue can be uncovered’.

I purchased Fantastic Night as part of Oxfam’s wonderful 2016 Scorching Summer Reads campaign. I was already familiar with Zweig’s work, and remember how enraptured I was when reading the excellent The Post Office Girl some years ago. Fantastic Night provides a mixture of novellas and short stories, many of which I hadn’t come across before.

I purchased Fantastic Night as part of Oxfam’s wonderful 2016 Scorching Summer Reads campaign. I was already familiar with Zweig’s work, and remember how enraptured I was when reading the excellent The Post Office Girl some years ago. Fantastic Night provides a mixture of novellas and short stories, many of which I hadn’t come across before.

It’s always going to be difficult to review a book about such a sickening and notorious crime as the massacre which happened on the island of Utoya in July 2011, and the bomb attack which happened in central Oslo just beforehand. Norway is one of my favourite countries, and Oslo is certainly one of the most peaceful and friendly places I have ever visited. I was even more shocked, therefore, when I learnt about Breivik’s crime. What occurred was reported in the British media, but relatively few details emerged about the trial. When I spotted One of Us in Fopp, I decided to pick it up to learn as much as I could. The fact that it is written by Asne Seierstad also swayed me, as I very much enjoyed her fascinating The Bookseller of Kabul when I read it a few years ago.

It’s always going to be difficult to review a book about such a sickening and notorious crime as the massacre which happened on the island of Utoya in July 2011, and the bomb attack which happened in central Oslo just beforehand. Norway is one of my favourite countries, and Oslo is certainly one of the most peaceful and friendly places I have ever visited. I was even more shocked, therefore, when I learnt about Breivik’s crime. What occurred was reported in the British media, but relatively few details emerged about the trial. When I spotted One of Us in Fopp, I decided to pick it up to learn as much as I could. The fact that it is written by Asne Seierstad also swayed me, as I very much enjoyed her fascinating The Bookseller of Kabul when I read it a few years ago.

Black Eyed Susans by Julia Heaberlin ***

Black Eyed Susans by Julia Heaberlin ***