Tag Archives: Kirsty

Three Recommended Books

Here is a collection of three quite different books, which I read recently, and very much enjoyed. I apologise for my lack of full reviews for these titles, but life has been very busy of late, and I just can’t keep up! Regardless, I highly recommend picking these up (especially if you have a little more time than I do!).

Swimming in the Dark by Tomasz Jedrowski

Set in early 1980s Poland against the violent decline of communism, a tender and passionate story of first love between two young men who eventually find themselves on opposite sides of the political divide—a stunningly poetic and heartrending literary debut for fans of Andre Aciman, Garth Greenwell, and Alan Hollinghurst.

When university student Ludwik meets Janusz at a summer agricultural camp, he is fascinated yet wary of this handsome, carefree stranger. But a chance meeting by the river soon becomes an intense, exhilarating, and all-consuming affair. After their camp duties are fulfilled, the pair spend a dreamlike few weeks camping in the countryside, bonding over an illicit copy of James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room. Inhabiting a beautiful natural world removed from society and its constraints, Ludwik and Janusz fall deeply in love. But in their repressive communist and Catholic society, the passion they share is utterly unthinkable.

Once they return to Warsaw, the charismatic Janusz quickly rises in the political ranks of the party and is rewarded with a highly-coveted position in the ministry. Ludwik is drawn toward impulsive acts of protest, unable to ignore rising food prices and the stark economic disparity around them. Their secret love and personal and political differences slowly begin to tear them apart as both men struggle to survive in a regime on the brink of collapse.

Shifting from the intoxication of first love to the quiet melancholy of growing up and growing apart, Swimming in the Dark is a potent blend of romance, post-war politics, intrigue, and history. Lyrical and sensual, immersive and intense, Tomasz Jedrowski has crafted an indelible and thought-provoking literary debut that explores freedom and love in all its incarnations.

A Feather on the Breath of God by Sigrid Nunez

From Sigrid Nunez, the National Book Award-winning author of The Friend, comes A Feather on the Breath of God, a mesmerizing story about the tangled nature of relationships between parents and children, between language and love.

A young woman looks back to the world of her immigrant a Chinese-Panamanian father and a German mother. Growing up in a housing project in the 1950s and 1960s, she escapes into dreams inspired both by her parents’ stories and by her own reading and, for a time, into the otherworldly life of ballet. A yearning, homesick mother, a silent and withdrawn father, the ballet–these are the elements that shape the young woman’s imagination and her sexuality.

The Scent of Flowers at Night by Leila Slimani

‘Night is the land of reinvention, whispered prayers, erotic passions. Night is the place where utopias have the scent of the possible, where we no longer feel constrained by petty reality. Night is the country of dreams where we discover that, in the secrecy of our heart, we are host to a multitude of voices and an infinity of worlds…’

Over one night, alone in the Punta della Dogana Museum in Venice, Leila Slimani grapples with the self as it is revealed in solitude. In a place of old and new, she confronts her past and her present, through her life as a Moroccan woman, as a writer, and as a daughter. Surrounded by art, she explores what it means to behold and clasp beauty; enveloped by night, she confronts the meaning of life and death.

One From the Archive: ‘The Lady and the Unicorn’ by Rumer Godden ****

I read this again recently, and was charmed by it all over again.

Rumer Godden’s The Lady and The Unicorn, which was first published in 1937, is the 630th entry upon the Virago Modern Classics list. As with The River and The Villa Fiorita, both republished by Virago at the same time, The Lady and The Unicorn includes a well-crafted and rather fascinating introduction penned by Anita Desai.

After setting out the author’s childhood, lived largely in India, Desai goes on to write about the influences which drove Godden to write over sixty acclaimed works of fiction, for both children and adults. Desai states that Godden ‘cannot be said to have been ignorant, or unmindful, of her society and its role in India. In no other book is this made as clear’ as it is in this one, a novel written ‘in the early, unhappy days of her first marriage’. Desai then goes on to write that ‘the contact with her students [at the dance school which Godden opened in Calcutta], their families and her staff taught her a great deal about the unhappy situation of a community looked down upon both by the English and by Indians as “half-castes”‘. The Lady and The Unicorn faced controversy upon its publication, with many English believing her ‘unfairly critical of English society’, and others viewing ‘her depiction of Eurasians’ as cruel. Her publisher, Peter Davies, however, deemed the novel ‘a little masterpiece’.

The Lemarchant family are Godden’s focus here; ‘neither Indian nor English, they are accepted by no-one’. They live in the small annex of a fading ‘memory-haunted’ mansion in Calcutta. The widowed father of the family is helped only by ‘auntie’ and a servant of sorts named Boy, an arrangement which causes misery for all: ‘There were so many ways that father did not care to earn money that the girls had to be taken at school for charity and the rent was always owing… No matter how badly he [father] behaved they [auntie and Boy] treated him as the honourable head of the house, and auntie complained that the children did not respect him as they ought’. The way in which the family unit is perceived within the community is negative, and often veers upon the harsh: ‘The Lemarchants are not a nice family at all, they cannot even pay their rent’ is the idea which prevails.

The three daughters of the Lemarchant family could not be more different; twins Belle and Rosa are often at odds with one another, and the youngest, Blanche, is treated no better than an outcast. Blanche is described as ‘the family shame, for she was dark. Suddenly, after Belle and Rosa, had come this other baby like a little crow after twin doves. Auntie said she was like their mother, and they hated to think of their mother who was dead and had been dark like Blanche. Belle could not bear her, and even Rosa was ashamed to be her sister’. Of the twins, Godden writes that Rosa, constantly overshadowed by her twin sister, ‘could never be quite truthful, she had always to distort, to embroider, to exaggerate, and if she were frightened, she lied’. The family in its entirety ‘were sure that Belle was not good, and yet at home she gave hardly any trouble; it was just that she was quite implacable, quite determined and almost fearless… Belle did exactly as she chose. When she was crossed she was more than unkind, she was shocking’. The divisions within the family therefore echo those which prevail in society.

The sense of place is deftly built, particularly with regard to the house in which the Lemarchants live: ‘There was not a corner of the house that Blanche did not know and cherish, all of them loved it as if it were their own; that was peculiar to the Lemarchants, for the house did not like its tenants, it seemed to have some strange resentment’. Of their surroundings, of which the girls know no different, Belle sneers the following, exemplifying her discontent: ‘We know a handful of people in Calcutta and most of them are nobodies too. What is Calcutta? It is not the world’. There is not much by way of plot here, really, but the whole has been beautifully written, and the non-newsworthy aspects of the girls’ lives have been set out with such feeling and emotion.

The Lady and The Unicorn is a captivating novel, which captures adolescence, and the many problems which it throws up, beautifully. Part love story and part coming-of-age novel, Godden is shrewd throughout at showing how powerful society can be, and how those within it often rally together to shun those ‘outsiders’ who have made it their home.

Six Lesser-Known Books I Would Recommend

Longtime readers of The Literary Sisters will know that I don’t tend to read a lot of popular books, unless I have heard excellent things about them from my most trusted resources. Instead, I tend to seek out the more unusual; those books which have slipped under the radar somewhat, and are lesser-known than the popular newly released fiction being spoken about everywhere. In that vein, I wanted to collect together six lesser-known books which I have very much enjoyed over the last year or so, and which I haven’t seen publicised much, if at all.

Islands of Abandonment: Life in the Post-Human Landscape by Cal Flyn

Investigative journalist Cal Flyn’s Islands of Abandonment, an exploration of the world’s most desolate, abandoned places that have now been reclaimed by nature, from the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea to the “urban prairie” of Detroit to the irradiated grounds of Chernobyl, in an ultimately redemptive story about the power and promise of the natural world.

Under the Stars by Matt Gaw

Moonlight, starlight, the ethereal glow of snow in winter… When you flick off a switch, other forms of light begin to reveal themselves.

Artificial light is everywhere. Not only is it damaging to humans and to wildlife, disrupting our natural rhythms, but it obliterates the subtler lights that have guided us for millennia. In this beautifully written exploration of the power of light, Matt Gaw ventures forth into darkness to find out exactly what we’re missing: walking by the light of the moon in Suffolk and under the scattered buckshot of starlight in Scotland; braving the darkest depths of Dartmoor; investigating the glare of 24/7 London and the suburban sprawl of Bury St Edmunds; and, finally, rediscovering a sense of the sublime on the Isle of Coll.

Under the Stars is an inspirational and immersive call to reconnect with the natural world, showing how we only need to step outside to find that, in darkness, the world lights up.

How to Walk on Water and Other Stories by Rachel Swearingen

In this spellbinding debut story collection, characters willingly open their doors to trouble. An investment banker falls for a self-made artist who turns the rooms of her apartment into eerie art installations. An au pair imagines her mundane life as film noir, endangering the infant in her care. A son pieces together the brutal attack his mother survived when he was a baby. These stories bristle with menace and charm with intimate revelations. Through nimble prose and considerable powers of observation, Swearingen takes us from Chicago, Minneapolis, and Northern Michigan, to Seattle, Venice, and elsewhere. She explores not only what it means to survive in a world marked by violence and uncertainty, but also how to celebrate what is most alive.

Five Tuesdays in Winter by Lily King

By the award-winning, New York Times bestselling author of Writers & Lovers, Lily King’s first-ever collection of exceptional and innovative short stories

Told in the intimate voices of unique and endearing characters of all ages, these tales explore desire and heartache, loss and discovery, moments of jolting violence and the inexorable tug toward love at all costs. A bookseller’s unspoken love for his employee rises to the surface, a neglected teenage boy finds much-needed nurturing from an unlikely pair of college students hired to housesit, a girl’s loss of innocence at the hands of her employer’s son becomes a catalyst for strength and confidence, and a proud nonagenarian rages helplessly in his granddaughter’s hospital room. Romantic, hopeful, brutally raw, and unsparingly honest, some even slipping into the surreal, these stories are, above all, about King’s enduring subject of love.

A Crooked Tree by Una Mannion

A haunting, suspenseful literary debut that combines a classic coming of age story with a portrait of a fractured American family dealing with the fallout of one summer evening gone terribly wrong.

It is the early 1980s and fifteen-year-old Libby is obsessed with The Field Guide to the Trees of North America, a gift her Irish immigrant father gave her before he died. She finds solace in “The Kingdom,” a stand of red oak and thick mountain laurel near her home in suburban Pennsylvania, where she can escape from her large and unruly family and share menthol cigarettes and lukewarm beers with her best friend.

One night, while driving home, Libby’s mother, exhausted and overwhelmed with the fighting in the backseat, pulls over and orders Libby’s little sister Ellen to walk home. What none of this family knows as they drive off leaving a twelve-year-old girl on the side of the road five miles from home with darkness closing in, is what will happen next.

A Crooked Tree is a surprising, indelible novel, both a poignant portrayal of an unmoored childhood giving way to adolescence, and a gripping tale about the unexpected reverberations of one rash act.

Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning by Cathy Park Hong

Poet and essayist Cathy Park Hong blends memoir, cultural criticism, and history to expose the truth of racialized consciousness in America. Binding these essays together is Hong’s theory of “minor feelings.”

As the daughter of Korean immigrants, Cathy Park Hong grew up steeped in shame, suspicion, and melancholy. She would later understand that these “minor feelings” occur when American optimism contradicts your own reality—when you believe the lies you’re told about your own racial identity.

Hong uses her own story as a portal into a deeper examination of racial consciousness in America today. This book traces her relationship to the English language, to shame and depression, to poetry and artmaking, and to family and female friendship in a search to both uncover and speak the truth.

‘Quicksand’ by Nella Larsen ****

I read Nella Larsen’s novel, Passing, some years ago, and found it both moving and thought-provoking. I have been meaning to read Quicksand, the first of Larsen’s novels to be published during her lifetime, ever since, but as ever, it has taken me quite a while to get around to doing so.

A classic of the Harlem Renaissance genre, Quicksand begins in the 1920s, and follows protagonist Helga Crane, who teaches at an all-Black school in the Southern USA, in the fictional town of Naxos. Helga has always been treated poorly because of the colour of her skin, and ‘has long had to fend for herself’. Following a disagreement in her workplace, she moves, first to Harlem, New York, and then to Copenhagen, Denmark, to stay with a kindly aunt. Here, ‘she attempts to carve out a comfortable life and place for herself, but ends up back where she started, choosing emotional freedom that quickly translates into a narrow existence.’ Passing also incorporates the story of a second woman; she and Helga meet one another in later life, after losing track following a childhood friendship. Her friend is ‘passing’ as a white person, living in an all-white community, and keeping this enormous secret from her family.

I found the novel’s opening extremely evocative: ‘Helga Crane sat alone in her room, which at that hour, eight in the evening, was in soft gloom. Only a single reading lamp, dimmed by a great black and red shade, made a pool of light on the blue Chinese carpet, on the bright covers of the books which she had taken down from their long shelves, on the white pages of the opened one selected, on the shining brass bowl crowded with many-colored nasturtiums beside her on the low table, and on the oriental silk which covered the stool at her slim feet.’ I appreciate the rich detail which Larsen weaves through Quicksand; it adds another layer to the story in itself.

Larsen pays so much attention to the scenes and settings which her characters inhabit. She also expertly builds up Helga’s character, so that she appears as a wholly three-dimensional being. Early in the novel, Larsen goes on, for example, to describe the following: ‘She loved this tranquility, this quiet, following the fret and strain of the long hours spent among fellow members of a carelessly unkind and gossiping faculty, following the strenuous rigidity of conduct required in this huge educational community of which she was an insignificant part.’ Helga is introduced as ‘a slight girl of twenty-two years, with narrow, sloping shoulders and delicate but well-turned arms and legs,’ and ‘with skin like yellow satin’. She goes on to demonstrate Helga’s steadfastness and determination, as well as the difficulty of fitting in with those around her which she constantly feels.

There are some happier moments in Helga’s life: ‘New York she had found not so unkind, not so unfriendly, not so indifferent. There she had been happy, and secured work, had made acquaintances and another friend. Again she had that strange transforming experience, this time not so fleetingly, that magic sense of having come home. Harlem, teeming black Harlem, had welcomed her and lulled her into something that was, she was certain, peace and contentment.’

I loved the way in which Helga’s relationship to the city changes from one season to the next; this was a really effective part of the narrative. Larsen writes: ‘As the days became hotter and the streets more swarming, a kind of repulsion came upon her. She recoiled in aversion from the sight of the grinning faces and from the sound of the easy laughter of all these people who strolled, aimlessly now, it seemed, up and down the avenues.’ Larsen goes on: ‘She was drugged, lifted, sustained, by the extraordinary music, blown out, ripped out, beaten out, by the joyous, wild, murky orchestra. The essence of life seemed bodily motion.’

The character progression here is excellent, and Larsen was rather clever in moving Helga to Copenhagen. The ‘othering’ which she experiences here is quite different; she is seen, in the upper class society in which her white aunt and her husband move, as: ‘… attractive, unusual, in an exotic, almost savage way, but she wasn’t one of them. She didn’t at all count.’ Her aunt convinces her not to hide away; she implores Helga to wear bright colours, and show off her figure, which she is so used to disguising from attention in the USA. Larsen goes on: ‘Incited. That was it, the guiding principle of her life in Copenhagen. She was incited to make an impression, a voluptuous impression. She was incited to inflame attention and admiration. She was dressed for it, subtly schooled for it.’

Quicksand, first published in 1928, includes such interesting explorations of self and identity. It feels rather ahead of its time in many respects. Larsen is not shy about probing the depths of her protagonist, mining a complex range of emotions and feelings. There is a real immediacy to the story, and I found myself really caught up in Helga’s life. I can’t say I particularly liked Helga, but I did find her a well-constructed, realistic character, with a lot of depth to her.

One From the Archive: ‘The Vet’s Daughter’ by Barbara Comyns *****

First published in 2014.

The Vet’s Daughter, which has been turned into both a play and a musical, has just been reissued by Virago, along with two of Comyns’ other novels, Sisters by a River and Our Spoons Came From Woolworths. The novel was first published in 1959, and as well as featuring an introduction written by Comyns herself, this new edition contains an introduction by Jane Gardam, who sets the scene of both the author and her work very nicely indeed. Gardam calls this, Comyns’ fourth work, her ‘most startling novel… the first in which she shows mastery of the structures of a fast-moving narrative… [It] is not about “enchantment”, it is about evil, the evil that can exist in the most humdrum people’.

The opening line alone is intriguing: ‘A man with small eyes and a ginger moustache came and spoke to me when I was thinking of something else’. Our narrator, Alice Rowlands, lives in ‘a vet’s house with a lamp outside… It was my home and it smelt of animals’. Her father’s tyrannical cruelty is present from the first page. When describing her mother, Alice says, ‘She looked at me with her sad eyes… Her bones were small and her shoulders sloped; her teeth were not straight either; so if she had been a dog, my father would have destroyed her’. In fact, many of the similes throughout are related to animals – for example, ‘holding up her little hands like kitten’s paws’, and ‘her lifeless hair… was more like a donkey’s tail’. An unsettling sense of foreboding is built up almost immediately, and much of this too has some relation to the animals which fill the house and surgery: ‘Before the fireplace was a rug made from a skinned Great Dane dog, and on the curved mantelpiece there was a monkey’s skull with a double set of teeth’, and ‘The door was propped open by a horse’s hoof without a horse joined to it’.

Alice is seventeen years old, and her present life in ‘the hot, ugly streets of red and yellow houses’ in London is interspersed with memories of her mother’s upbringing on a secluded farm in Wales. Alice’s dreams, which far surpass her sad reality, consist of the following: ‘Some day I’ll have a baby with frilly pillows and men much grander than my father will open shop doors to me – both doors at once, perhaps’. Alice and her mother are both terrified of her father – her mother tells her daughter that ‘He was a great and clever young man, but I was always afraid of him’ – and his presence fills the novel even when he is away from home: ‘We heard Father leave the house and it became a peaceful evening, except that we had a mongoose in the kitchen’. The fact that her father is even mentioned in the book’s title demonstrates the level of control he has over her. To add to their troubles, Alice’s mother becomes ill. Desperate Alice laments somewhat over her fading life, telling us that, ‘I felt a great sorrow for her and knew that she would soon die’, and ‘Autumn came and Mother was still dying in her room’. Her father, as is to be expected, exhibits his usual cruelty when faced with the news; he sends a man in to measure his wife for her coffin whilst she is still alive.

Throughout, Alice is an incredibly honest narrator. One gets the sense that we as readers see her world exactly as she does, and that nothing has been altered before it reaches the page. All of the characters throughout feel so real, and Comyns has built them up steadily and believably. Their actions do not feel forced, which demonstrates Comyns’ deftness of touch. Whilst The Vet’s Daughter is a sad novel – well, a novella, really – what sadness there is is interspersed with humour and wit. The balance between the two has been met beautifully. For example, just after Alice’s mother’s death, Comyns describes the way in which ‘Already the parrot had been banished to the downstairs lavatory, and in its boredom had eaten huge holes in the floor’.

Tumultuous relationships between characters are portrayed with such clarity of the human condition throughout the book, and the story is both powerful and memorable in its tale and its telling. Alice faces more challenges than the average teenager, but her strength of mind and the way in which she always tries to make the best out of a bad situation endear her to the reader. Her honesty shines through, particularly as her story progresses: ‘I wrote a letter to Blinkers. Although it wasn’t very long, it took me two weeks to write because it was the first one I’d ever written – there had been no one to write to before’. The Vet’s Daughter is a beautifully and sympathetically written book, which takes many unexpected twists and turns, and presents the reader with a story which is likely to stay with them for an awfully long time.

‘The Besieged City’ by Clarice Lispector ****

Clarice Lispector is an author whose work I have loved for some years, now. Recently, I was able to get my hands on a newly-published copy of her third novel, The Besieged City, which was originally published in 1948. The Besieged City was translated into English by Johnny Lorentz, and was not published until 2019.

Our protagonist is a young woman named Lucrécia Neves; she is described as ‘vain, unreflective, insolently superficial, almost mute. Brought up in a small Brazilian town, she soon finds herself grown, and becomes the ‘worldly wife of a rich man.’ Lucrécia spends her time seeking perfection, ‘to be an object, serene, smooth, beyond the burden of words or even thought itself.’

The novel begins at an undefined point during the 1920s, a time which marks a point of change in the township of São Geraldo. The town is undergoing a process of modernisation, much to the chagrin of some of its residents: ‘And there were also people who, invisible in the former life, were now gaining a certain importance, simply for refusing the new age.’ We first meet Lucrécia when São Geraldo gathers to celebrate its saint. The first description given of her is as follows: ‘Beneath her hat Lucrécia’s dimly lit face sometimes looked delicate, sometimes monstrous. She was peeking out. Her face had a sweet watchfulness, without malice, her dark eyes peeking at the fire’s mutations, her hat with the flower.’

As a character, Lucrécia has been wonderfully, and believably, built. Lispector tells us: ‘Lucrécia Neves needed countless things: a checkered skirt and a little hat of the same material; for a long time now she’d been needing to feel how others would see her in a checkered skirt and a hat, a belt right on her hips and a flower in the belt: dressed like that she’d look at the township and it would be transformed…

That’s how you composed a vision. The girl didn’t have any imagination but a watchful reality of things that was making her almost sleepwalk; she was needing things in order for them to exist.’ All that Lucrécia is occupied with is people taking notice of her; her vanity consumes almost her every thought. Later, Lispector comments: ‘Just as she’d never needed intelligence, she’d never needed truth; and any picture of her was clearer than she was.’

Lispector builds tension exquisitely. There are points in the novel which I found quite unsettling from the opening scene, and this disturbing tension which Lispector so expertly builds can be found throughout The Besieged City. As a reader, I highly appreciate the amount of often unusual detail Lispector chooses to include: ‘The house where she lived was pierced with pipes and windows, which made it very weak – the girl was going up the steps that were trembling with the final vibrations of the bells.’ Her prose is enchanting, with an otherworldly quality to it: ‘Things were growing with deep tranquility. São Geraldo was displaying itself… The girl was looking while standing, constant… Everything was incomparable. The city was a manifestation. And on the bright threshold of the night all of a sudden the world was the orb. On the threshold of the night, an instant of muteness was the silence, appearing was an appearance, the city a fortress, victims were offerings. And the world was the orb.’

I really admire the layers within Lispector’s novels; she sees, at once, her characters set against others, and the places in which they live, as well as giving one a constant awareness of the wider social and political context. In this manner, elements of this novel can be a little confusing, given the way that Lispector moves forward in time from one chapter to the next; delineations in changes of period are not detailed immediately, and it can therefore be a little perplexing to keep everything straight. It is a strange novel in places, but I found it wholly compelling.

The Besieged City is a novel which is said to have ‘obsessed’ its author. I agree with the novel’s blurb; it is unlike any other book of Lispector’s which I have read to date, although the remarkable writing is distinctly hers. I do not feel as though Lispector, an incredibly clever writer, gets anywhere near as much attention as she deserves. There are those who probably won’t get on with the pacing of her writing, or her detailed prose, which is not always straightforward, and often includes unusual sentence construction. However, this is a novel that I would highly recommend to any keen reader, who wants to read something rewarding and different.

‘No Place to Lay One’s Head’ by Françoise Frenkel ****

No Place to Lay One’s Head is an incredibly important piece of social history. Françoise Frenkel, a Jewish woman, was forced to flee from Berlin, where she had opened the city’s first French bookshop in 1921, during the Second World War.

Originally planning to open a French bookshop in Poland, she found the market so saturated that she went to Berlin instead. Frenkel’s bookshop attracted ‘artists and diplomats, celebrities and poets’, and brought her ‘peace, friendship and prosperity’. Of her customers, Frenkel notes: ‘Over time I grew to know my bookish clientele. I would try to fathom their desires, understand their tastes, their beliefs and their leanings, try to guess at the reasons behind their admiration of, their enthusiasm for, their delight or displease with a work.’

Despite booming business, and a slew of regular customers, Frenkel’s dream was crushed following Kristallnacht. After nobody stood up for her, and she felt her position becoming more and more precarious, Frenkel was advised by the French consulate to make the move to France just a few weeks before the start of World War Two. On the eve of her departure, she tells us: ‘That night, I understood how I had been able to withstand the oppressive atmosphere of those last years in Berlin… I loved my bookstore the way a woman loves, that is to say, truly.’

When Paris, the city in which she has made her home, is bombed, Frenkel has to flee once again, first to Avignon, and then to Nice. Of the Nazi Occupation, she describes: ‘What an image, the birth of this monstrous and ever-growing human termite colony spreading swiftly through the country with a sinister grinding of metal; a colony with the potential for incalculable collective strength.’ Horrified by the scenes she sees, she goes into hiding, and ‘survives only because strangers risk their lives to protect her.’

The detail which Frenkel includes about the myriad ways in which life is changed is both important, and appreciated by this reader. When she is residing in Nice, she comments on the difficulties which she faces every single day, often to do the simplest things, like buy food: ‘The background to this existence was the waiting, a canvas upon which ever more meagre hopes and ever gloomier thoughts together embroidered their nostalgic motifs.’

I warmed to Frenkel immediately, finding her at once dreamy and pragmatic. On the very first page of No Place to Lay One’s Head, for example, she describes the following: ‘For my sixteenth birthday, my parents allowed me to order my own bookcase. To the astonishment of the joiner, I designed and had built a cabinet with glass on all four sides. I positioned this piece of furniture, conjured from my dreams, in the middle of my bedroom.’ Of the books which took pride of place here, she writes: ‘Balzac came dressed in red leather, Sienkiewicz in yellow morocco, Tolstoy in parchment, Reymont’s Paysants clad in the fabric of an old peasant’s neckerchief.’

No Place to Lay One’s Head is a remarkable book. We sadly know very little about Frenkel herself, aside from basic biographical details, such as that the memoir was written ‘on the shores of Lake Lucerne’ between 1943 and 1944. However, I found myself utterly fascinated by her; by her choices, and her words. Her memoir, which was originally published in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1945, was rediscovered in an Emmaus Companions charity jumble sale in 2010, and was republished in its original French. The memoir is now being translated and into numerous languages for the first time. Stephanie Smee’s English translation is fantastic; nuanced and incredibly readable. I read every sentence with a deep, consuming interest. There is a real immediacy to what Frenkel relays, an urgency.

Novelist Patrick Modiano, who penned the preface, comments that from his own research, Frenkel ran her bookshop with her husband, Simon Ratchenstein, ‘about whom she says not a word in her book’. Indeed, I got the impression throughout that Frenkel was an incredibly independent woman, almost astonishingly so for the time in which she was living. Modiano goes on: ‘What makes No Place to Lay One’s Head unique is that we cannot precisely identify its author. This eyewitness account of the life of a woman hunted through the south of France and Haute-Savoie during the Occupation is all the more striking in that it reads like the testimony of an anonymous woman, much as A Woman in Berlin… was thought to be for a long time.’

Of course, No Place to Lay One’s Head is heartbreaking and harrowing. However, Frenkel is sure to include comic moments from time to time. Her writing is so controlled, and she was always aware of which tone to strike. The thought of her family, many of whom she receives no news about throughout her narrative, keeps her going, and stops her from giving up.

By far the biggest emotion Frenkel shares is gratitude toward all of those who helped her. Even in instances where she is betrayed, she displays very little anger or resentment. I will close my review with the rather moving dedication she added to her absorbing memoir: ‘I dedicate this book to the MEN AND WOMEN OF GOODWILL who, generously, with unfailing courage, opposed the will to violence and resisted to the end.’

Some Favourite Books From My Childhood

First published in 2014.

I thought that it would be a good idea to create a blog post about all of the books which I adored as a child, and naturally, there are many of them. I have used my Library spreadsheet (a big list of all of the books which I’ve read during my lifetime) as inspiration.

The Big Surprise (Topsy and Tim #2) by Jean Adamson – I used to read the Topsy and Tim books religiously when I was in infant school, and they were the first books I got to when I moved myself up a reading group, much to my parents’ amusement. In my infant school library, we had a series of wooden boxes on legs, and each of them was painted in a different colour. The books within each had a corresponding coloured sticker upon their spine. When I had made my way through the colour which I had been assigned, I would move myself up so that I had more books at my disposal. I think, in this way, that I reached the books for the most advanced readers when I was still in the middle of Year One. I also learnt recently that Jean Adamson is a relatively local author to me, and I would have found such a fact terribly exciting when I was younger. Topsy and Tim is a lovely series of books, and this was my particular favourite.

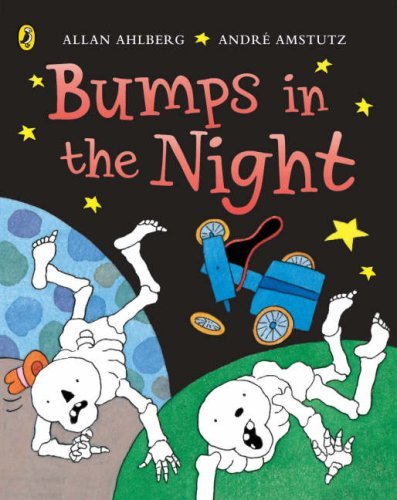

Funnybones by Allan Ahlberg – This book had an accompanying cartoon, which I am sure that many people of my age still remember the opening rhyme to. The concept was quite simple: in a dark, dark town, in a dark, dark street, in a dark, dark house, in a dark, dark cellar, lived three skeletons – Big Skeleton, Little Skeleton, and their dog. Each story featuring the trio was so fun, and I loved the illustrations. Even though the very idea of living skeletons who enjoy playing tricks on people seems a little odd to me as an adult, something about it really worked, and for this reason, Funnybones and the rest of the books in the series will definitely be read (and the cartoon shown) to my future children, who will hopefully find it as amusing and memorable as I still do.

The Bear Nobody Wanted by Janet and Allan Ahlberg – Janet and Allan Ahlberg were my literary heroes when I was small, and I loved reading all of their books. The Bear Nobody Wanted is one which remains vivid in my mind. The story begins as a sad one, but it has a delightful ending, and it certainly made me treasure my soft toys all the more.

The Jolly Postman, or Other People’s Letters, The Jolly Pocket Postman and The Jolly Christmas Postman by Janet and Allan Ahlberg – I still remember these books with such fondness. Each had a plethora of small envelopes inside, in which there were tiny letters which the Jolly Postman was delivering all around town. I am certain that the stories would still absolutely delight me as an adult, and I am very excited about the possible prospect of re-reading them far into the future.

Each Peach Pear Plum by Janet and Allan Ahlberg – Definitely one of the most adorable simple picture books that there is. I vividly remember reading it over and over again before I could even read its words.

Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen – I still absolutely adore these tales, and was lucky enough to drag my boyfriend around the Hans Christian Andersen Museum in Copenhagen last year. I cannot pick a favourite story as I did love so many of them, but as it is still essentially wintertime, I shall say that ‘The Snow Queen’, and its beautiful television adaptations, is at the very pinnacle of my treasures list.

The Lighthouse Keeper’s Lunch by Ronda and David Armitage – Such an absolutely charming book, which I remember adoring. I found out last year that there is an entire series of these books, and am hoping that my library has them all in stock so that I can joyfully discover the Lighthouse Keeper all over again.

The Flower Fairies by Cicely Mary Barker – It goes without saying that I absolutely adored these books. Which little girl didn’t? I would happily gaze at the illustrations for hours, and read the lovely accompanying rhymes.

The Complete Brambly Hedge by Jill Barklem – Surely the most adorable series of books, Brambly Hedge centered around a group of woodland creatures who wore the most adorable clothing, and were real characters in themselves. I am longing to rediscover these lovely tales once more.

Peter Pan by J.M. Barrie – Quite honestly, I could gush about this charming book for hours. If you haven’t read it before, please, go and do so. It is beautiful, magical and filled with adventure – for me, the very cornerstones of marvellous children’s literature.

Madeline by Ludwig Bemelmans – Everyone who knows me tends to know how much I absolutely adore the Madeline books, and Madeline herself as a character. These tales are all told in rhyme, and centre upon a children’s orphanage in Paris, in which Madeline lives with eleven other little girls and their guardian, Miss Clavel. Bemelmans’ illustrations are utterly charming, and he effortlessly captures the excitement and adventure which his little heroine encounters along the way.

Two Books About Belonging: ‘The Unpassing’ and ‘Do Not Say We Have Nothing’

I had been wanting to read both of these books – Chia-Chia Lin’s The Unpassing, and Madeleine Thien’s Do Not Say We Have Nothing – for such a long time, but as is often the case for a self-confessed bookworm, other works took my attention. It so happens that I ended up reading both of these novels within quite a short window of time. Whilst they are decidedly different books in some ways, their core themes of belonging and identity are similar, so I felt grouping them together in a review would make sense.

The Unpassing is narrated by Gavin, a boy living in rural Alaska, who contracts meningitis when he is just 10 years old. When he awakes from his coma, he is told that his younger sister, 4-year-old Ruby, was also infected, and had passed away. Their family is Taiwanese, and soon realise that the American dream which they had chased across the ocean is something of a myth. I very much enjoyed Gavin’s first person perspective, which is infused with wisdom beyond his years. When he first awakes, and is told about Ruby’s fate, he expresses: ‘It began to seem that everything I had ever touched was missing. Or at least the things most familiar to me were gone.’

A lot about this novel appealed to me, as its themes are those I very much enjoy exploring in my reading: family, wilderness, grief, displacement, poverty, and belonging. Lin’s writing is descriptive and expressive, and I immediately got a feel for the way in which Gavin, somewhat isolated from his peers, lives: ‘Thirty miles outside Anchorage, our small house sat by itself at the end of a short gravel road… To the back and sides were spruce woods that had lived through world wars, the gold rush, homesteading. But in a country where we had no ancestors, in a state only twenty-some years old, the past felt irrelevant to us.’ This is a novel absolutely filled to the brim with sadness, but Lin’s writing has an almost hypnotising quality. However, for a reason I cannot quite pin down, I did not enjoy The Unpassing quite as much as I expected to.

Madeleine Thien’s Do Not Say We Have Nothing has received numerous accolades, and was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2016. The novel is told using interlinked stories, a technique which is one of my favourites in fiction. Do Not Say We Have Nothing opens in 1990 in Vancouver, Canada, where young protagonist Marie and her widowed mother ‘invite a guest into their home: a young woman who has fled China in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square protests.’ In her present-day narrative, Marie is a mathematics professor; throughout the novel, she recollects how vastly her life changed when she was just 10, and Ai-ming arrived: ‘Ai-ming’s presence made everything unfamiliar, as if the walls were crawling a few inches nearer to see her.’

I really liked the nods throughout to Marie’s identity and culture, and the differences between her life and her parents’: ‘My father spoke Mandarin and my mother Cantonese, but I was fluent only in English.’ This linguistic barrier holds some challenges for Marie; she feels as though she cannot quite understand, or grasp, things. I appreciated Thien’s inclusion of so much historical detail here, which made the reading experience rich. The novel is a little slow-going at times, but the author wonderfully captures so much, particularly with regard to landscape and emotion.